If you think of early Gothic women writers, your mind probably leaps to Mary Shelley. She does tend to get all of the attention: her own books, her own films, cameos in Doctor Who… you can’t help but be happy that a woman writer is getting the attention she deserves.

It’s clear why Mary Shelley’s become a Gothic pinup. You don’t get much more Goth than sex on your mother’s grave and keeping your husband’s heart in a drawer. And that’s not to mention the fact that she came up with one of the most famous Gothic novels of all time. It doesn’t hurt that she did it in a ghost story competition with Lord Byron and Percy Shelley where she showed them exactly where they could stick their monstrous egos.

But that brings me to my axe to grind, the Gothic fly in my witch’s broth. As we dust Mary Shelley off for the umpteenth time and parade her once more into the limelight, we’re losing sight of the fact that she was far from alone. She was one of a pantheon of some of the most badass women writers of all time. Early Gothic literature heroines whose lives and legacies are more thrilling than fiction. Spare a thought for the other real life Gothic heroines of that period. Making publishing history, crossing war-torn Europe, seducing princes, becoming an underground powerhouse in the male-dominated theology industry, defying society at every turn and figuring as some of the key thinkers of early feminism. Let me introduce you to five other real-life heroines of the Gothic who deserve just as much attention as Mary Shelley.

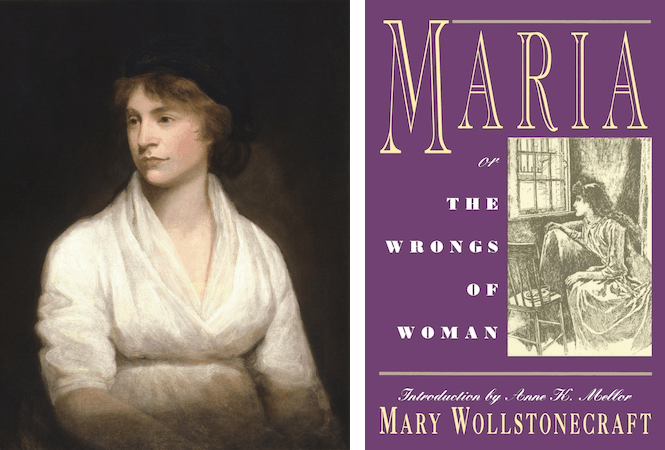

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 – 1797)

Gothic Credentials: First let me introduce you to Mary Shelley’s even more famous mother (well, at the time). The writer of, among other things, the seminal feminist work Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), Wollstonecraft’s work might seem a world away from the ‘frivolity’ of the Gothic. But her last, unfinished work, was the eminently Gothic Maria, or The Wrongs of Women (1798). As with all her work, Mary Wollstonecraft wasn’t pulling any punches in the book. She recognised that underlying, encoded, half-hidden heart of the early women’s Gothic—the fact that men are the real threat—and made it, in her own work, impossible to ignore. She opens strong:

ABODES OF HORROR have frequently been described, and castles, filled with spectres and chimeras, conjured up by the magic spell of genius to harrow the soul, and absorb the wondering mind. But, formed of such stuff as dreams are made of, what were they to the mansion of despair, in one corner of which Maria sat, endeavouring to recall her scattered thoughts!

Her heroine Maria has been locked up by her husband for all those inconvenient little characters traits, like having a character. As Wollstonecraft makes abundantly clear, the castles and tyrannies that have encoded patriarchal oppression in earlier books haven’t got anything on the contemporary realities of women’s lives and their erasure in law once married.

Heroine Credentials: If you think that her daughter was the heroine of her own Gothic life, you should hear about her mother. She never saw a rule she didn’t want to break, and she put her money where her mouth was when it came to her feminist writings. She lay across her mother’s bedroom door to protect her from an abusive husband, helped her sister escape an unwanted marriage and took on some of the biggest political and philosophical names of her day. Passionate female friendships, love affairs, a move to France to experience the revolution, a narrow escape with her child, solo business trips to Scandinavia, attempted suicide by laudanum and drowning, a place as one of the leading lights of literary society in London and an eventual marriage to the equally scandalous political philosopher, William Godwin, for the sake of the as yet unborn Mary Shelley—her life would make the subject of several excellent novels!

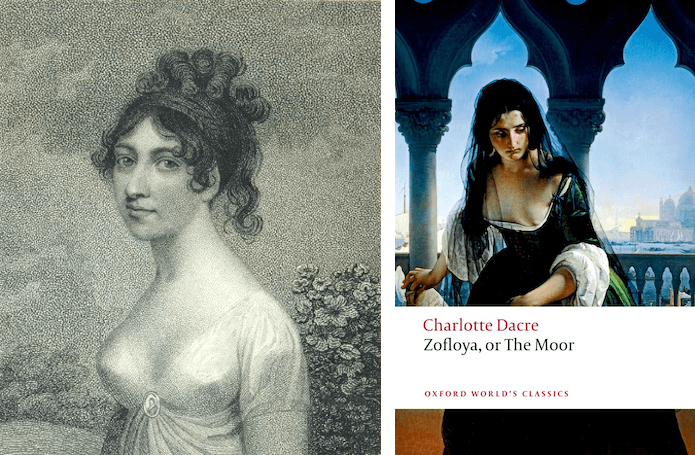

Charlotte Dacre (1771 – 1825)

Gothic Credentials: Charlotte Dacre was a Gothic poet and author whose work was considered eminently unsuitable for fostering good morals in its female readers at the time. Always a good sign. Unlike many of the women writers of the early Gothic, she has no time for mealy-mouthed heroines following all the rules. Indeed, in her most famous work Zofloya (1806), said weeble-heroine is gleefully hurled off a cliff. What Dacre brings us are some good old-fashioned murder ladies. Well… new-fashioned in her time. Zofloya is all about the voluptuous and half-demonic Victoria and her dealings with the all-demonic Zofloya—the devil disguised as a handsome Moorish servant. Although Victoria is suitably punished for her transgressions at the end, Dacre revels in depicting female desire (for a man of colour no less—scandalous) and you can’t help wondering if she isn’t rather on the devil’s side.

Heroine Credentials: Very little is still known of Charlotte Dacre. In her published works though she created herself as the Gothic heroine of her own creation. Frequently publishing under the pseudonym ‘Rosa Mathilda’, she used Gothic portraiture to create an image which has outlived many of the actual facts of life.

What we do know about Charlotte Dacre is that she was the daughter of the famous, or infamous, moneylender and political agitator John King. Born to Sephardic Jewish parents, little is known about Dacre’s own religious affiliations except that she was eventually buried in the Church of England. She is noteworthy though for her success not only as a woman writer but as a Jewish writer and one, moreover, with a scandalous personal history. She married her husband newspaper editor Nicholas Byrne in 1815. He was a widower. Nothing so shocking there. Except they already had three children, all born before the death of his wife. It seems reasonable to suggest that the transgressive exploration of women’s desire in her books isn’t a million miles from her own experiences of living outside of the narrow rules of conduct of the time. Unlike her heroines though she had a happy ending — she certainly wasn’t thrown of any cliffs by the devil, at least.

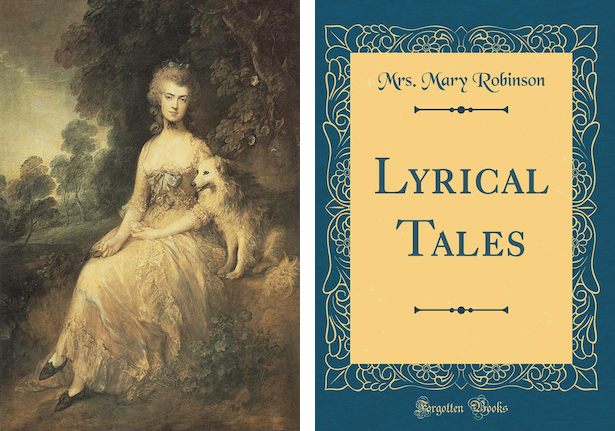

Mary Robinson (1757 – 1800)

Gothic Credentials: Mary Robinson is most famous for her more ‘respectable’ work, her poetry, specifically her Lyrical Tales (1800). The Gothic manages to seep in there as well though in The Haunted Beach—a tale of a murdered man and a ghostly crew. She also wrote a number of Gothic novels in the 1790s including Vancenza (1792) and Hubert de Severac (1796) and wrote her own posthumously published autobiography as a Gothic text. Like Charlotte Dacre’s Gothic women, Robinson’s are sexually experienced but remain the heroines of their own stories rather than the monsters that haunt them.

Heroine Credentials: Mary Robinson was a celebrity in her day for more than her writing (for which she was also justly famed). She was an actress, an early feminist, and celebrity mistress, known as the ‘English Sappho’. Her most famous conquest was the Prince Regent (later George IV) whose portrait she wore encrusted with diamonds throughout her life but who she did not hesitate to blackmail for £5000 pounds when he cast her off. It was marriage to a wastrel which initially brought her to the stage. Married young, she followed him to debtors’ prison, took on the mantle of bread earner with both transcription jobs and the sale of her poetry. The Duchess of Devonshire (of The Duchess fame) was her patron. Later she took to the stage to support her daughter and there won the attention of the prince causing one of the greatest scandals of its time. In 1783 she remained paralysed after an unidentified illness and turned seriously to writing to support herself. She was a noted feminist, a supporter of the French Revolution and a prolific writer. Unstopped and unstoppable by all the vicissitudes and turnabouts of her truly Gothic career.

Anna Letitia Barbauld (1743 – 1825)

Gothic Credentials: Anna Letitia Barbauld may be famed more for her literary criticism and children’s literature than for Gothic writing but she still influenced the genre. With her brother John Aiken she wrote the essay ‘On the Pleasure Derived from Objects of Terror’ with the fictional fragment ‘Sir Bertam.’ Although short, her theorisation of the pleasure and value of terror was an important early basis for a defence of the Gothic.

Heroine Credentials: Barbauld, on the surface, seems respectably dull. Rather than a Gothic rebel, she is famous as an educator of the young, a writer of theological materials and dedicated wife to a man who grew increasingly unstable over the course of their marriage. That all ended, of course, when he chased her round the dinner table with a knife and she escaped by leaping hotfoot out of the window. He was institutionalised soon after. However, there’s far more to Barbauld than the party line. She was born into a Dissenting family—one whose religious beliefs placed them outside the Anglican Church, separated from the rights and privileges the law gave to those adhering to the state church, That Dissenting lineage was a sure sign that she wasn’t ever going to be quite on board with the status quo. Thanks to her father’s teaching and her own keen mind, she received an education far better than women of her day could generally boast. While her poetry, her fictional collaborations with her brother and her theological writing may seem tame at first glance, closer inspection sees not only the radical sympathies of her poetry (including its abolitionist stance) but the daring of her theological work. In a time when women were practically banned from the theological sphere, Barbauld became an influential figure…sneakily. Her work had a widespread and international impact, but was ‘veiled’ in ‘acceptable works’ such as children’s literature, devotions, and poetry. (I take this idea of ‘veiled theology’ from Natasha Duquette’s excellent Veiled Intent (2016).)

Ann Radcliffe (1764 – 1823)

Gothic Credentials: Empress, queen, mother of the Gothic, Radcliffe was the most influential Gothic writer of her day. She wrote six novels, including the astronomically famous Mysteries of Udolpho (1794); a book of travel writing; copious diaries and assorted poetry. She was also one of the most financially successful with Udolpho bought for a staggering £500—an unheard of sum. There is a mystery which dogs her legacy though. Why, in the height of her success, did she stop publishing 30 years before her death?

Heroine Credentials: Representations of Radcliffe veer between the dull (her husband’s account of her dutiful wifing) to the Gothically extravagant. The rumour circulated in her lifetime that she stopped publishing because she had been driven mad by her own writing. Supposedly, she was kept at Haddon Hall (which you may know as the location where Thornfield is usually filmed in Jane Eyre adaptations). Not true, though that would have been truly Gothic. Radcliffe retired from publishing to live a fairly secluded life with her editor husband, possibly due to illness. However, she continued an avid traveller—a travelling heroine if you will. (Thanks to Ellen Moers’ Literary Women for the term!) Her biography is full of excerpts from her diaries, evidence of the aesthetic appreciation which is, after all, the proper accoutrements of any serious heroine. But the carefully selected snippets that her husband passed to her biographer hide the reality which we can discern peeping through her own published travel-writing. Her account of her travels through Holland and Germany carefully encodes her highly engaged critical commentary but also reveals a woman as curious and immune to danger as her own heroines. What her measured prose almost hides is the fact that she was travelling through a war zone. The descriptions of towering carts of wounded and dying men, bombardments and ruined cities are mentioned so momentarily as to almost pass us by at times. But like her heroines, Radcliffe travelled just on the edge of danger, keeping strictly to the rules of decorum while taking her life in her hands as what seems to be a matter of course. Paul Feval pays homage to the adventurer Radcliffe in his highly readable vampire romp The Vampire City (1867). Move over Buffy, Ann was the first slayer!

Of course, these are not the only real life Gothic heroines. There were many more each deserving far more attention than they get. The women writers of the early Gothic were taking the publishing world by storm, forging careers, casting off shackles left, right and centre. But we only have time for so much. Next time, though, when you’re making your next film, writing your next book, or putting together your next blog—spare a thought for someone other than Mary Shelley. Gothic heroines come in a range of flavours and we really ought to let a few more come out and enjoy themselves in the sun for a little while.

Dr. Sam is an associate lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan university and has their PhD in Theology and Early British Gothic. They run the Romancing the Gothic online courses and can be found in their leisure time reading, scarfing biscuits and watching Murder Ladies with Swords flounce across the screen.